Writing about jazz eludes me. I don’t know if there’s an intellectual flex that has carved up so much real estate in America’s purest art form which feels like a wall, or the truth that I cannot speak to its music in musician’s terms. Whatever it is, pretty much any time I’ve been given a chance to write about jazz (music review, essay, writing assignment from a professor/mentor curious about my take on Dave Brubeck) I have simply balked at it. In a lot of ways, I think that the insecure space I hold within my own sense of authority is so unabashedly naked when it comes to writing jazz that there has been a general anxiety.

I’ve been spending my mornings as of late with James Kaplan’s outstanding 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool. The book moves like a series of photographs, composed biographical snapshots of the three principal drivers of Miles' iconic Kind of Blue. When I mean composed here, I mean scattered, like a scrapbook or album that tucks in newspaper clippings and other ephemeral markers of time within its pages until it becomes less about the subjects and more about the before/during/aftermath of the Kind of Blue itself. These bits and pieces, when folded between the vellum and adhesive pages of the album, are loose and ask us to pull them out, unfold their copy and lay them alongside Kaplan’s book. Sometimes their digression is too easy to ignore, often it fills in blanks we didn’t know we needed filled in…but what is the center of this scrapbook? What moves in and out of our focal point?

Maybe Miles is the center of the narrative. Even in the photographs where he is not in the field of vision, you can feel his eyes scaling the viewfinder, or his scissors cutting out articles from Downbeat or the New York Times. It’s all tenuous, of course, and while I have not finished the book, I already know the story as its sound for some is the default association with the word jazz itself.

These bits and pieces, when folded between the vellum and adhesive pages of the album, are loose and ask us to pull them out, unfold their copy and lay them alongside Kaplan’s book.

In a way, 3 Shades of Blue serves as a reminder to me that music — and especially jazz — is not an intellectual chase in and of itself. Those musicians recording in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey or 30th Street Studios in Manhattan were not interested in the academic discourse that tried to follow or construct sense around their art. Maybe it’s because we are so apt to hear these names tossed around the academy rather than the barroom, or maybe the record collectors who wander into a jazz section are more interested in reissues than new artists…I don’t know. Maybe the timelessness of Trane or Miles or Monk or Bird (who also show up within Kaplan’s pages) makes the new practitioners feel like a moot point, that there is nothing but tradition.

That doesn’t make sense either, especially when you see where musicians like Kamasi Washington or Yusef Dayes take jazz, AND how hip hop has become its spiritual heir as America’s latest artistic gift to the world (one that just celebrated its 50th anniversary last year).

Maybe there’s something to that point of innovation which offers the casual fan a kernel of truth. My takeaway has always been that jazz is at its most vital (like any art form) when it is its most experimental. The traditional guard that saw folks like Brandford and Wynton Marsalis as keepers of the faith in the 80s may have more in line with wanting jazz to stay conservative, a fixed foot of a compass where the circle has limits to its expansion capacity. Can it be that desire to stand still and not push forward (at least in popular culture) has helped to set jazz in amber? Is this fact also the reason why those who sought to push the art forward found and find themselves spilling over into worlds outside the stated genre? Even Miles Davis was spurred on by both record label (who were more likely looking to recoup Miles’ album advances), wife Betty Marby, and former drummer Tony Williams to explore beyond the modal and free, pioneering jazz/rock fusion with albums like In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew.

I mean, this singular sense of what a music can/cannot be is not new. Look at country music as the most homogeneous and “traditional” of genres and you’ll see one that’s mainstream machinations have kept experimentation out of its original recipe because Morgan Walen’s commercial appeal will fill a bar or arena or empty a beer cooler of Coors light sixers at a steady blurry pace. I’m sure there’s experimental country music out there, but where? Even when someone like Beyonce makes a country-infused record (and let’s not get started on the whitewashing of country music’s history) she’s not found anywhere on the CMA Awards.

---

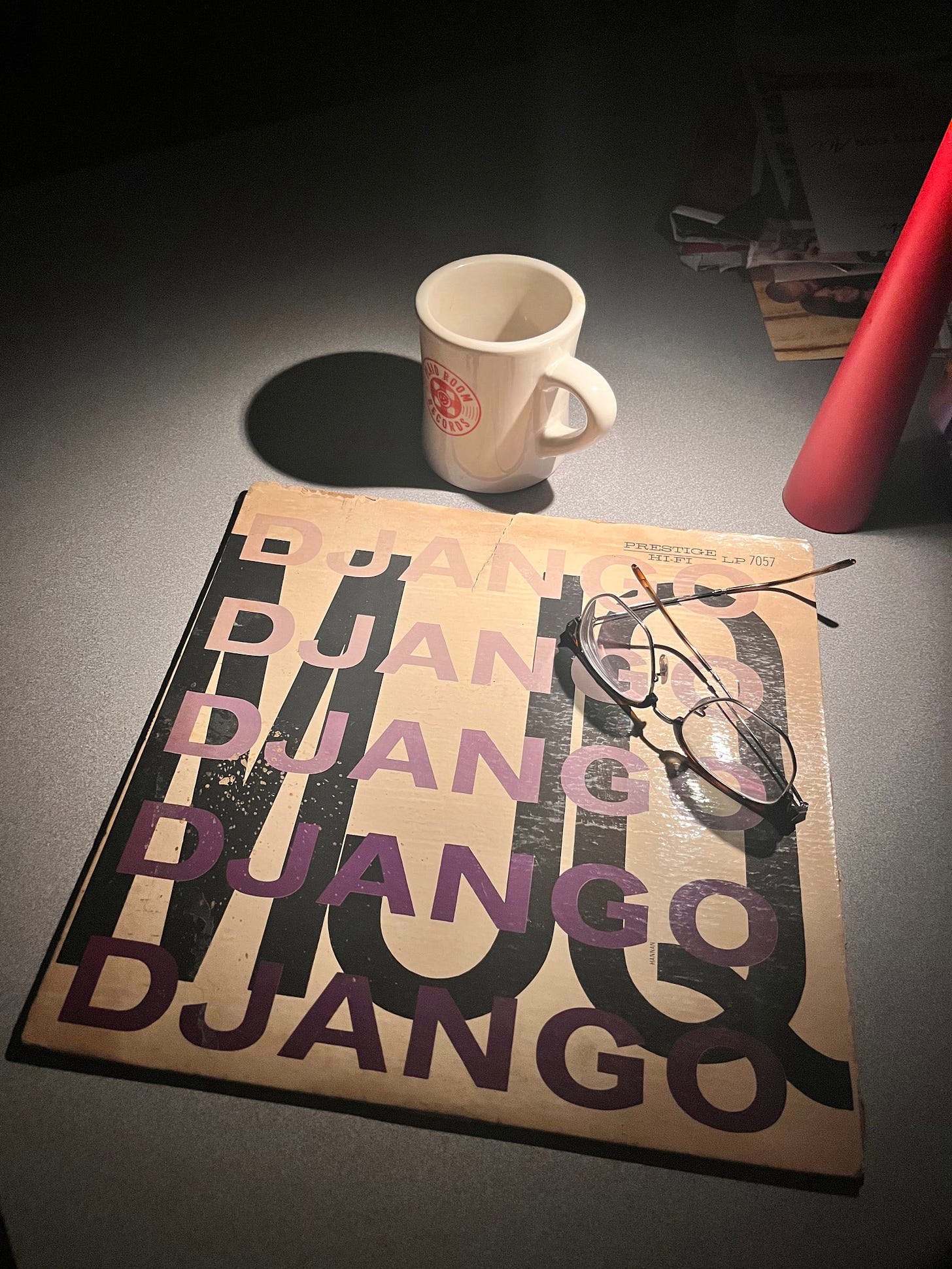

Over the weekend, I found a weatherworn first pressing of Django by the Modern Jazz Quartet at Revival Records in Eau Claire. The album has an inch long tear across the front of the jacket, the snow white backdrop has yellowed and darked to match the pale purple and gray gradient wordmark. These type of records cause me to pause when I see them in a record store, and more often then not, I’ll buy them with little to no thought to the actual condition or playability of the record. It feels like an artifact from a well-lived life. Sometimes these damaged albums are saddled with neglect rather than love, but this copy of Django has a story housed in its original paper sleeve that I will only be able to speculate on and never know. A good mystery and journey has led this first pressing on Prestige Records (actually collected sides from the original dying 10” format to 12” LP) to find its way into my collection. It’s not all perfect fidelity and unspoiled mint grades for me. Some days, it’s all about being a steward to another life, a well-soundtracked one at that.

In this possession, I find my way into talking about jazz, I guess.

It’s a record that resonates, sonically and emotionally for me. I first bought the record on CD when I was a college freshman on a whim. More than likely it was a random and lonely Friday night early on in my first semester, the purchase more an afterthought than premeditated. Not every record calls you from across a shop or enters your world from an open window or radio dial. I’d be lying if I told you if picking up Django was nothing more than knowing I wanted to hear some jazz and that’s it.

I do remember being struck by the lineup’s sound on first blush. It’s probably the first time I really listened to jazz and had those casual expectations both confirmed and challenged by the instrumentation. No trumpet, no sax, no brass or woodwind of any kind to be found here, just piano, vibraphone, bass, and drums.

Milt Jackson’s vibes rang out, turning icicles into honey and water. For me, the sound was equal parts fragile, warm, and rippling, all the while retaining its cool. Even as I struggled along as taking drum lessons and studying jazz percussion, it was clear to me that I had such a limited worldview to its potential.

The Modern Jazz Quartet felt instructive, but never academic. All these years later, being able to find Django on an equally random weekend in my (relatively new) life in another college town feels full circle. For me, there’s nothing scholarly to chase or defend in exploring sound. That might be the closest I’ve come to writing about jazz yet.